1840

The Founding

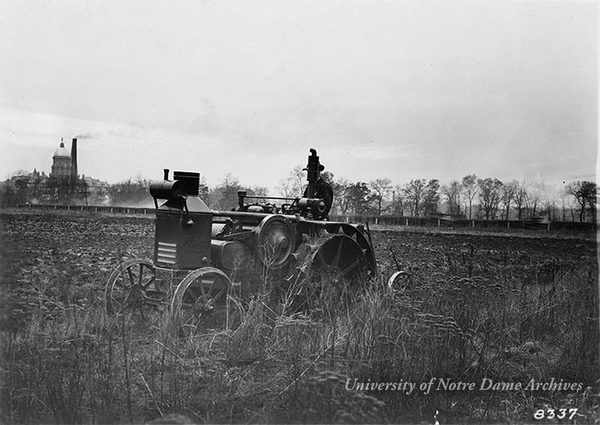

Then

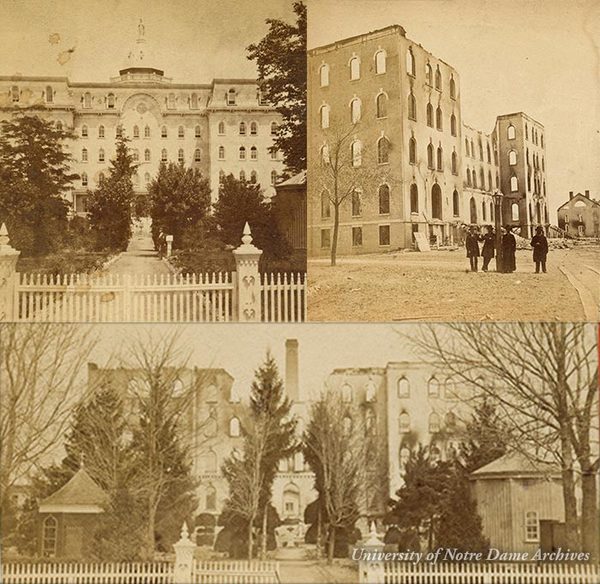

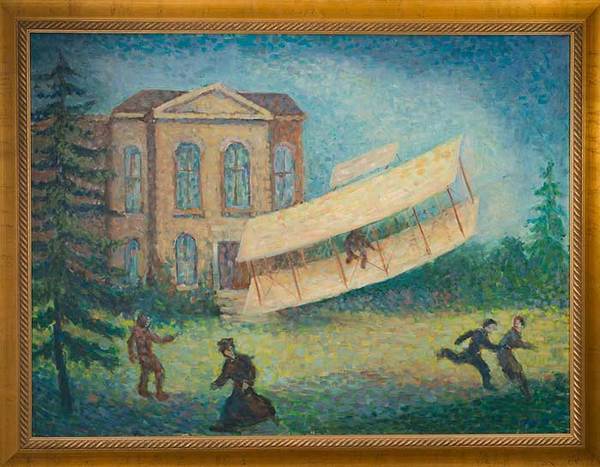

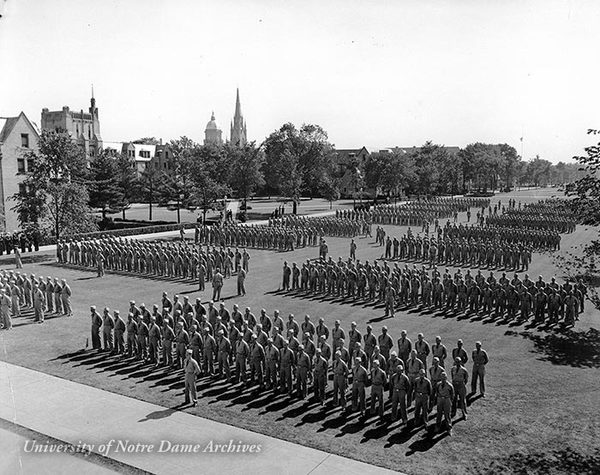

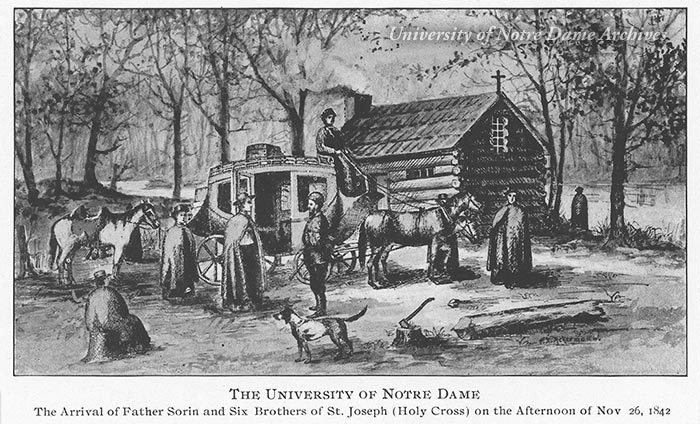

The story of Notre Dame begins in Le Mans, France, in 1840. That is when and where Blessed Basil Moreau, founder of a religious sect called the Congregation of Holy Cross, dispatched a young priest named Edward Sorin to the Diocese of Vincennes, Indiana to start a college. After spending a year in the southern part of the diocese, Fr. Sorin and seven Holy Cross brothers arrived on November 26, 1842, to a missionary outpost near South Bend, Indiana. There, they took possession of 524 snow-covered acres with two lakes.

The only shelter then standing on the site was a log chapel, which Fr. Sorin described in his journal: “an old log cabin, 24 × 40 feet, the ground floor of which answered as a room for a priest, and the story above for a chapel for the Catholics of South Bend and the neighborhood, although it was open to all the winds."

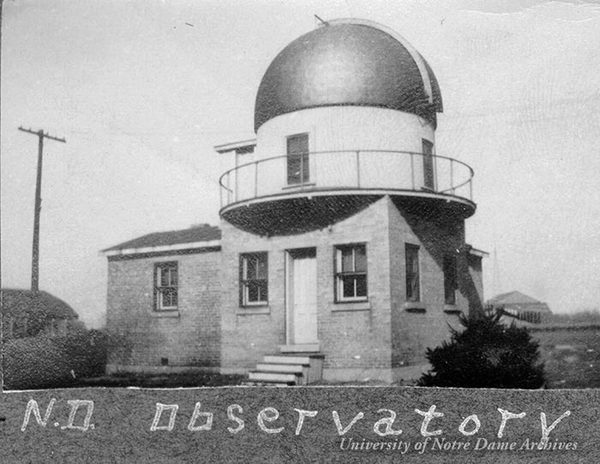

The place was meager at best, but Fr. Sorin envisioned then what he soon began to build and to call “L’Université de Notre Dame du Lac” (the University of Our Lady of the Lake), insisting that the new school would become “one of the most powerful means for good in this country."

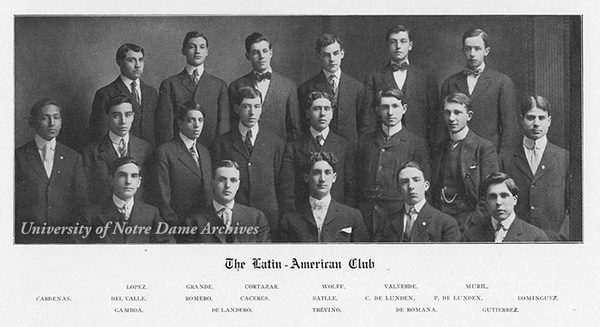

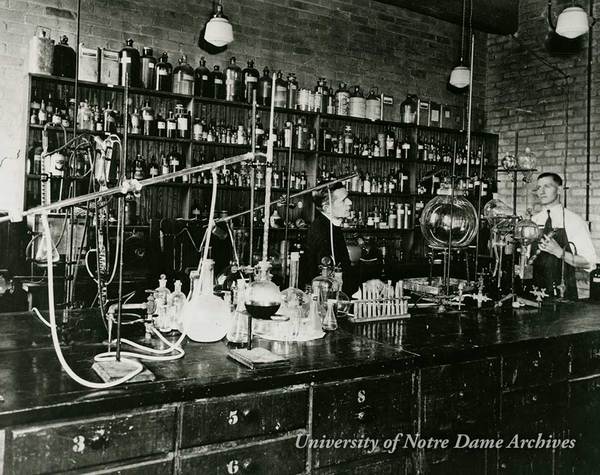

Now

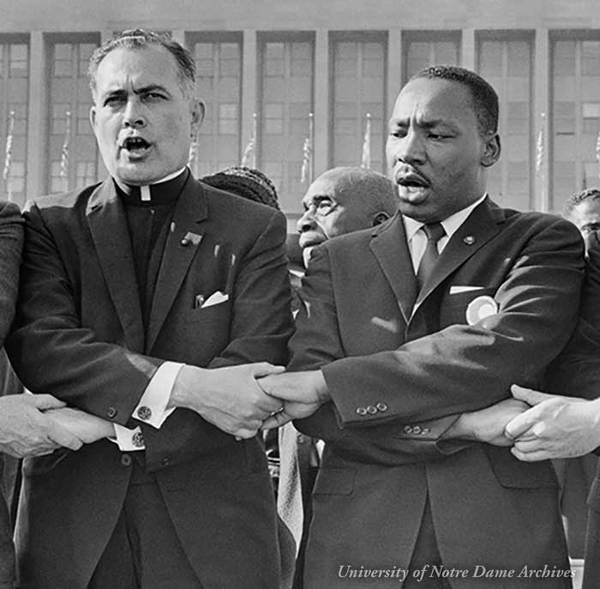

Today’s campus is 1,261 acres on which scholarly inquiry is rigorously pursued, informed by the University’s Catholic character. Yet the impact of Notre Dame is not just felt locally or regionally. The University is a globally recognized institution that strives to bring knowledge into service of justice for the benefit of all people. True to Sorin’s vision, the University of Notre Dame continues to remain steadfast in its spiritual and intellectual traditions.